It’s no secret that we live in a period overflowing with meteorological record-breaking events and abnormal weather. The latest of these — a historically strong El Niño event — may have come as a welcome relief to those on the Atlantic Coast (and not just those with a snowboarding holiday booked out west). Although an El Niño weather event occurs over the Pacific, the knock-on effects felt in the Atlantic usually mean a less active hurricane season.

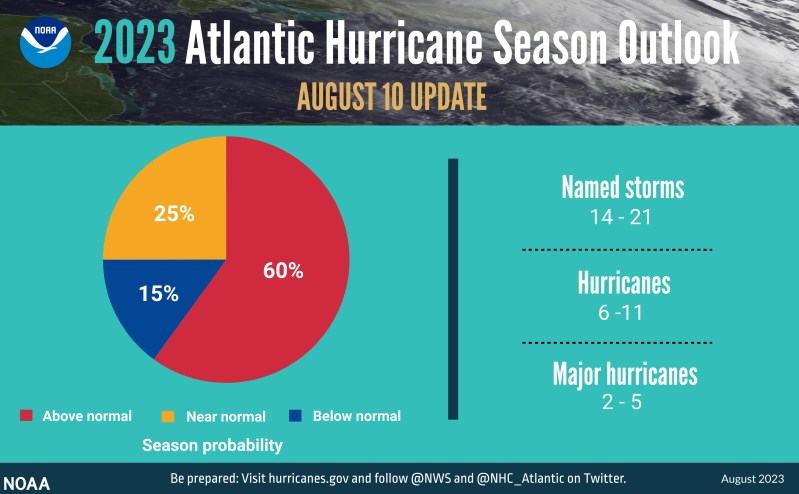

But not in 2023. Despite this historically strong El Niño weather system building over the Pacific, this Atlantic hurricane season — according to NOAA — has a 60% chance of above-average activity. While the typical hurricane season produces fourteen named storms, of which seven become hurricanes, this year could see as many as twenty-one named storms and more than ten hurricanes. So what’s different about this year compared with other El Niño hurricane seasons?

What effect does El Niño usually have on the Atlantic hurricane season?

Most people following the El Niño weather patterns are skiers or snowboarders looking for a winter season heaped in deep powder. El Niño events occur over the Pacific. A reduction in trade winds that blow warm west water along the equator prevents an upwelling of cool water, and as the Pacific warms, the West Coast sees an increase in wet weather. As this event often comes to a head in December, this precipitation falls as snow, leading to some historic skiing and snowboarding years.

During El Niño events, the air currents over the tropics alter and affect the conditions in the upper atmosphere. In turn, this increases wind shear — changes in the speed and direction of the wind — over the Atlantic, where these hurricanes form. In essence, the process tamps down the formation of a hurricane, never allowing it to build the necessary power. This isn’t to say that hurricanes can’t build in El Niño years, but that years with El Niño events usually coincide with below-average hurricane seasons.

What’s different about 2023?

It might not surprise you that just because El Niño historically means a less volatile hurricane season doesn’t mean that’s what’s happening this year. The difference in 2023 primarily comes from the fact that the Atlantic is experiencing record-warm sea surface temperatures caused in part by — you guessed it — climate change. Hurricanes forming over the Atlantic Ocean draw their power from the ocean’s heat, pulling moisture and energy directly from the water below. While often the wind shear of an El Niño event would help to lessen this, the effects are late in arriving.

This combination of forces has led forecasters to predict an active East Coast hurricane season. While this could mean the Atlantic coast is in for a rough ride, there are still factors to watch out for. Firstly, this is a prediction of hurricanes rather than specifically landfall hurricanes. Secondly, there is still time for the effects of El Niño to play a part in the 2023 hurricane season. Regardless, those on the East Coast should have a robust hurricane plan as the season continues.