Khalik Allah does not grant interviews. Not often. “Wikipedia got me a year older, so a lot of articles have copied that for the last two years,” the 35-year-old photographer says. He rarely posts on social media, and save for a flash sale from his photo agency, Magnum, he’s had a quiet year in his home in Rocky Point, N.Y. What’s that quote from Flaubert, regular and ordinary in your life so as to make violent art? “Just building quietly,” he says, “not really putting too much work out into the world at the moment, keeping more of a distance.

Related Guides

- Where to Find Artwork to Match Your Style

- Contemporary Artists You Need to Know

- Photography Tips for Beginners

“But I’ve still been shooting.”

Allah is a paradox in the fine art world. While many photographers transition to cinema, he began as a filmmaker whose photography was self-taught and came late, and at this point it has all but eclipsed his first career. In 2020, when pandemic concerns paused most creative work, Allah found himself invited to apply for admittance into Magnum Photos, the oldest photo agency in the world and arguably the most prestigious. “Joining Magnum is an incredible accomplishment, and I’m so grateful for it,” he says. “But I was going to continue doing that work that I’m doing regardless of whether [my work] blew up or not. Fortunately for me, it has, but I’m still remaining humble.”

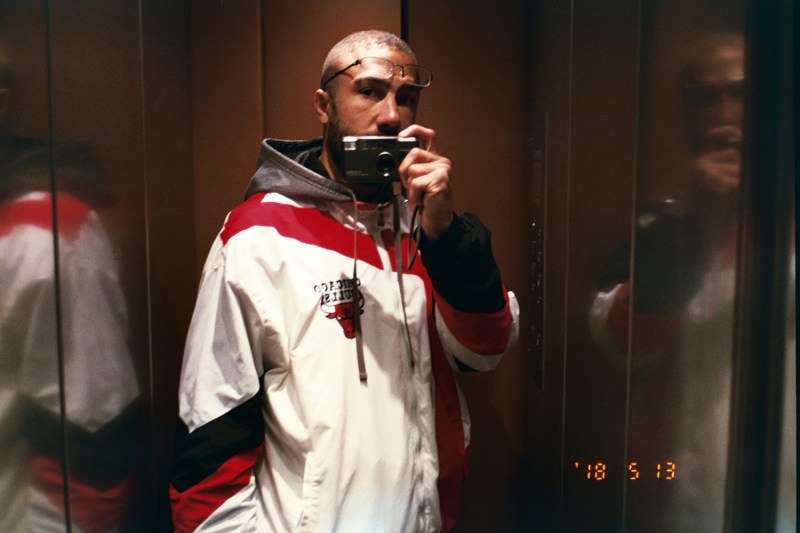

Allah speaks like this, displaying an internal balance akin to a kung-fu master, one leg raised, on a log, over a river. It’s a related metaphor, as his photography began when Wu-Tang Clan founding member GZA was scheduled to stop by his home for a documentary he was completing and Allah had to scramble for a camera to take a few stills. He asked his brother: “He said, ‘I don’t let people borrow my shit,’” Allah says, laughing. Necessity being the mother of invention, he flashed back to the family Christmases and vacations of his childhood. “I called up my pops, and I said, ‘Yo, remember that camera you used to shoot, that silver camera?’” That heavy, metallic body and manually manipulated lenses that ran off roll film and obscure batteries, the one without autofocus. It felt different from the plastic cameras he’d used. “Just the look of it is what pushed me into becoming a photographer,” he says.

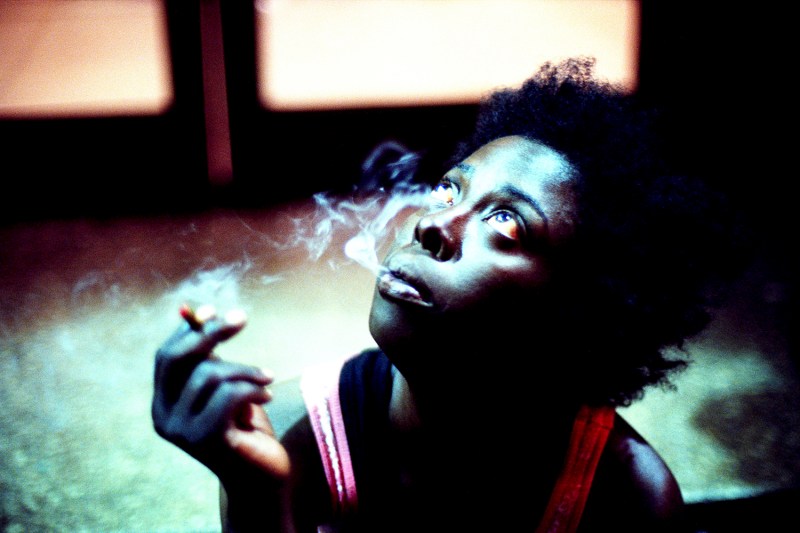

Despite the advancement of digital photography, in which new cameras are shoved into a frothing market clamoring over pixels and frame rates, Allah has continued to shoot 35-millimeter film in his documentary-style work. But even with the medium’s ongoing renaissance, he stays notably narrow: one camera, a Nikon; one lens, an old manual-focused prime; and one film stock, Kodak’s Portra 160. He processes and scans it himself, spending as much as an hour or two on a selected frame, and on the streets, his chosen milieu, he takes even more time cultivating relationships with his subjects, who become recurring characters in his body of work. “There’s a lot that goes into it, just gaining people’s trust and gaining permission to take photographs in this intimate sense,” he says. “If I mess up, it falls on me.”

The final part of the process is the print itself, about which he’s an ardent believer. He speaks of physical photos with a mysticism reserved for religious rites: “When you see things online, it’s easy to move on quickly — it’s just the nature of social media,” he says. “But I find when I’m in a gallery on exhibition and I’m looking at work, I stay with that picture. I may stand in front of it five or 10 minutes, and I remember those images differently.”

It’s extended into his street photography, and with camera and film, he heads out with a small portfolio of printed images. Approaching a new subject, he’ll pull out the photos, and if someone asks, he’ll give them away without a second thought, despite the fact that even his smallest prints fetch prices of a hundred dollars or more in fancy galleries. For Allah, it’s a means of establishing trust while simultaneously showing these people that he’s serious in his craft. “It’s helped me gain deeper access into the community that I photograph,” he says.

His own studio’s walls are a collage of items and images, the flotsam on the shore of a creative life: handwritten notes, cashed checks, film posters, and hip-hop records, along with pictures of Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, and John Coltrane. “Their lives, the tenacity, the fortitude,” he explains. They are symbols and inspiration. “I don’t even know who took those pictures, honestly.”

When others talk of his work, the word “cinematic” is thrown out in an effort to describe the darkness and contrast of his images; their bright, saturated colors; and his subjects, who often come from the lowest rungs of the societal ladder. But he loves the descriptor, as clichéd as some have made it, since his non-traditional path has trained in him to think of the 36 frames on every roll with the continuity of a film. Rather than being disjointed, they progress through the session, a beginning, a middle, and, by its end, they’ve elucidated their subject, offering his audience an intimate view and larger truths than mere silver grain and transparent acetate.

There’s a confidence, a solidity, required before one can teach. It’s obvious, in speaking with Allah, that he possesses an equilibrium that is rare. In 2017, at the encouragement of a mentor, he applied for admission to Magnum. He was rejected. In an industry thirsty for validation, his zen response stands in stark contrast to that of his peers. “Maybe my portfolio wasn’t ready at that time. Maybe I wasn’t ready for it in my life at that time, either,” he says. But his belief in his work never faltered, nor did it change to match what was saleable or what was perceived to be “Magnum.” He saw his work in his mind’s eye before the shutter was ever released and did not falter in his resolve. “What’s valuable is already inside me, and I’m not looking for external validation for my work. I’ve already accomplished so much and gotten so far just on my own, shooting from the heart.”

But so many words about his photos can be exhausting. Interviewing is exhausting. Talking on the phone so long, instead of peering at contact sheets with postage-sized photos, reviewing images that then require hours in refining, or leaving his studio to meet subjects and capture their visages in hundredths of a second, that is where Allah’s energy is needed. “There’s something in talking about work that’s difficult,” he says, coming to the end. “I want to allow my work to just speak for itself.”