When I was growing up, my brother wanted to take karate lessons, a specific term that became a generic word for all the martial arts taught in strip malls across America in the ’90s. He and my dad joined a “dojo” run by a “sensei” who was Irish and wore a white pajama “gi” cinched by a black belt embroidered with tiny characters that no one could read. Since my brother and I are a year apart and would do everything together, I started taking karate lessons which were not karate, but a Korean martial art that was taught by a guy who had never traveled to Asia. A few months later, my sister, who’d previously been taking gymnastics, was enrolled next to her two brothers. In hindsight, it was probably so my parents could save on gas.

Related

Karate was beautiful: the cadence and angles and synchronization of straight lines, limbs extended with centrifugal force and the pivot of hips, a kind of interpretive dance. But even back then, in the mid-’90s, the Ultimate Fighting Championship was shaking up everything about our ideas of martial arts. UFC’s concept was simple, and also the plot of the Jean-Claude Van Damme fighting movie Bloodsport: What if there were a tournament that pitted style against style to find out which was the best? What if Japan’s karate squares off against Israeli Krav Maga. What would happen if an Olympic wrestler fought a sumo wrestler? It was an exercise of excess, American ingenuity at its finest, with no holds barred and no strikes outlawed. Stick the two fighters in a cage that only opens when one guy submits or gets knocked out.

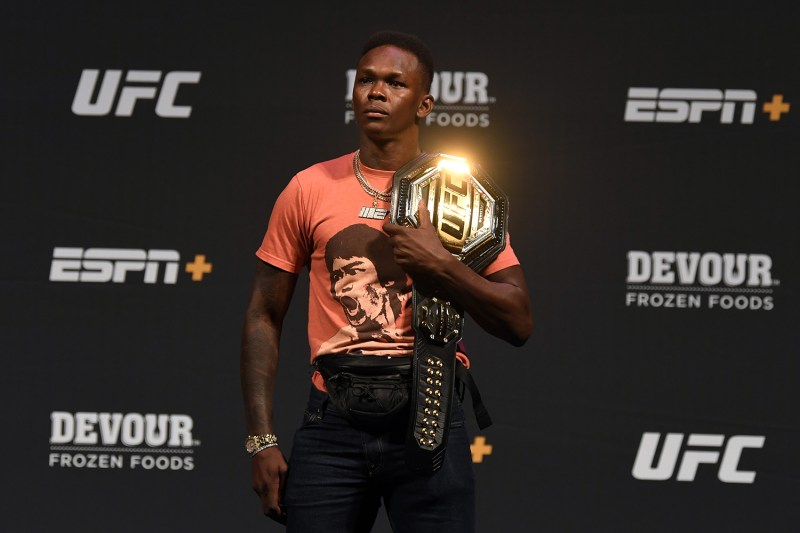

But the point of the words leading up to this is that Israel Adesanya, a Nigerian-born New Zealander and UFC Middleweight champ, is challenging the three-decades-long maxim of the sport of mixed martial arts, and when he contends for the Light Heavyweight title on Saturday, March 6, in Las Vegas, he’ll be continuing to revolutionize a sport built on revolution.

Hosted in Denver, Colo., in 1993, the UFC was originally decried by conservative politicians and fighting purists alike, and yet it spread like wildfire via VHS. The tournament’s first winner, Royce Gracie, choked out all comers with his family’s Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, which borrowed the name of a Japanese style of martial arts but had as much to do with it as an Irishman has teaching a Korean style in Detroit. Gracie’s grappling neutralized bigger, stronger men by hugging them to the ground and then chess-moving around to isolate vulnerable spots like the neck or appendage joints. And it made fools of every other martial art, whose practitioners seemed helpless as soon as they ended up on their backs. There were no more wheel kicks and wide stances. Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and grappling were revolutionary, forever changing combat sports, because they did away with artifice and beauty, creating a new philosophy that only included dirty, brutal, and efficient technique.

It is all so simple on paper and pixel, but no one has yet managed to solve the sphinx-like riddle of Adesanya. Around half his fights go the full three- or five-round distance, but unlike his opponents, Adesanya takes markedly less damage since his range is so much greater (artillery takes fewer casualties than infantry), and he’s nearly as pretty in the post-fight as he is in the weigh-in. In the fights where he does score the technical knockout via strikes, they’re either the sum total of head shots via punches or a head kick that feints toward the legs before question-marking its way to the temple. Between, he shimmies and goads and poses as if looking down from Olympus.

There have been plenty of champs that draw eyes from outside the sport — Conor McGregor, certainly, along with Chuck Liddell, Ronda Rousey, and Jon Jones, to name only a few. Like any other champ, Adesanya is very, very good, but how he’s very good is worth noting. A former professional kickboxer, he should be an easy meal for any wrestler or grappler in the Gracie mold, and in the modern era, every fighter is either a grappler or wrestler, so every fight should play out this way: tackle, ground-and-pound punches, fin. But Adesanya cannot be dropped. To even get close, opponents must thread the gauntlet of needle-precise fists and long kicks thrown from the dressing room. When opponents shoot, he sprawls or, most often, defends within the clinch, folding his incredibly long appendages into wedges that create space and eventually allow him to jog away. And then he’s regained distance, and a steady rain of punches and kicks to the face accumulates, and one finally makes everything go white and then black as his opponent keels over and the ref waves the match over.

Combat sports, like other contact sports, don’t often attract men of high character. But Adesanya, 31 and only three years into his UFC career, has the electricity of any of the previous or current greats and has avoided even a whiff of controversy. He boasts a perfect record within the octagon, and more than anything, he is a beautiful fighter to watch. In a sport that has eschewed style for substance from its inception, he proves that modern fighters can have both.

It should also be noted that Adesanya is a giant nerd in the same vein as writer Ta-Nehisi Coates. Adesanya, as potent and respected within his field, choreographs his walk-outs with Pokemon allusions, and his nickname, The Last Stylebender, is adapted from anime. It’s entirely possible that no one has ever tried to bully him, and it’s too late now.

On Saturday, fans like me will flash back to the strip malls of our youth, remembering the beauty of kicking and punching when Adesanya takes on Jan Blachowicz for the Light Heavyweight title. UFC 259 has a compelling card, which includes two other championship bouts, as well as the return of Islam Makhachev, an out-of-nowhere fighter who spent his COVID year whopping opponents like they were on an assembly line. But at the top of the card is the UFC’s brightest star, Israel Adesanya, taking on a Polish knockout artist and brawler on a four-fight win streak. Eyes are watching, waiting for the winner. But more than that, we’re waiting for the magic Adesanya has had since his debut, a distinct fighter that the never-seen-before sport has never seen before.

Editors' Recommendations

- 3 Reasons You Need to Watch UFC 287

- Why You Need to Watch Undefeated Khamzat Chimaev Take on Nate Diaz at UFC 279

- Peña vs Nunes 2 is Headlining UFC 277 — Here’s What Happened Last Time

- What Time is the UFC Fight Tonight? UFC 276 Schedule

- UFC 276 Could Have the Best Fight Card We’ve Seen in 2022